This blog post was written for the course "Current Issues in Global and EU Affairs", which took place from February 12-April 30, 2018.

|

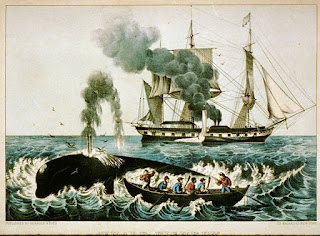

| A Currier & Ives print depicting a whaling expedition Image credit: Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons |

Stephanie Pettigrew and Elizabeth Mancke (2018) have suggested that Dano-Norwegian claims on Greenland fisheries shaped the early modern North-Atlantic geopolitics. It affected the establishment of European settlements in North America and their later integration into Euro-Atlantic economy.

In the 1550s, the early modern Swedish ethnographer and historian Olaus Magnus dedicated several chapters of his monumental work, A Description of the Northern Peoples, to the sea life and fishery in the Dano-Norwegian North Atlantic. Mixing a deep factual knowledge with legends and fantasy, he describes whaling methods and the unique usefulness of whale products. Olaus Magnus compares metaphorically whales and humans: They both travel across the ocean. However, whales migrate to reach their breeding places, while humans only follow their greed and foolishness.

Since the 18 century, whale oil was widely used as illuminants, lubricant, ambergris for perfumes, and baleen for umbrellas and corsets. It became an important source of hard currency for the New England colonies. Like the Dano-Norwegians, the British tried to monopolise whaling in North America, which forced the colonists to go further south.

Between 1814 and 1850, while British, French and Dutch whaling in North-Atlantic declined, the American whaling industry experienced its golden era. According to Derek Thompson, in 1846, American companies counted 640 whaling ships, three times as much as the rest of the world combined. At its height, the whaling industry contributed $10 million (in 1880 dollars) to GDP, making it the fifth largest sector of the US economy. The key to the success of the New England whalers was their global operation and higher risk taking: They entered the Pacific already at an early stage and established a network of whaling and trading stations in Africa, South America, Pacific islands, and especially Hawaii.

Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick (1851) is a monument over this era. Not unlike Olaus Magnus, he combines fiction, history, and ethnography with philosophical reflections over irrational drivers and self-destructing obsessions of humans. We encounter metaphors of people and whales, critics of slavery, and the image of a nation as a ship. The latter image is particularly echoed by Gilroy.

Since the discovery of petroleum oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania in 1859, the American whaling business declined. However, the network established by the New England whalers would be exploited by the US to maintain its dominance in the Pacific. Many decades later an attack on one of the Pacific naval bases would bring America back to European war. Probably neither Olaus Magnus, nor Melville could imagine the long term geopolitical consequences of the irrational passions of their whalers.

References:

- Paul Gilroy (1993), The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness

- Olaus Magnus (1555), Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus

- Stephanie Pettigrew & Elizabeth Mancke (2018), European Expansion and the Contested North Atlantic, Terrae Incognitae,

- Brian R. Pellar (2017), Moby-Dick and Melville’s Anti-Slavery Allegory, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan